The Problem with Dumping the Pump

The BWRX-300 uses natural circulation so that it can ditch pumps. But what if that’s a bad thing?

I’ve been on the record as calling GE Vernova’s BWRX-300 “the closest thing to a sure thing” in comparison to the current crop of Small Modular Reactors (SMRs). This is because — as GE relentlessly tells us — the BWRX-300 is just the tenth revolution of the tried-and-true Boiling Water Reactor (BWR).

“There’s no magic here; it’s all a boiling water reactor,” said Christer Dahlgren, principal engineer, in an interview with NEI.

But there is something that separates BWRX-300 from all the BWRs in operation…indeed from all other commercial reactors currently in service. You see, the BWRX-300, like the ESBWR (Economic Simplified Boiling Water Reactor) it was derived from, relies on natural circulation. They have done away with circulating pumps. You don’t need as many wires and piping and pumps with natural circulation, and there is a perception that it’s safer. So what’s the problem?

In the latest episode of Decouple, MIT’s Koroush Shirvan unpacks the consequences that are downwind to this decision.

“Passive circulation will make everything bigger,” said Shirvan, “in a Boiling Water Reactor, specifically, it is very harmful.”

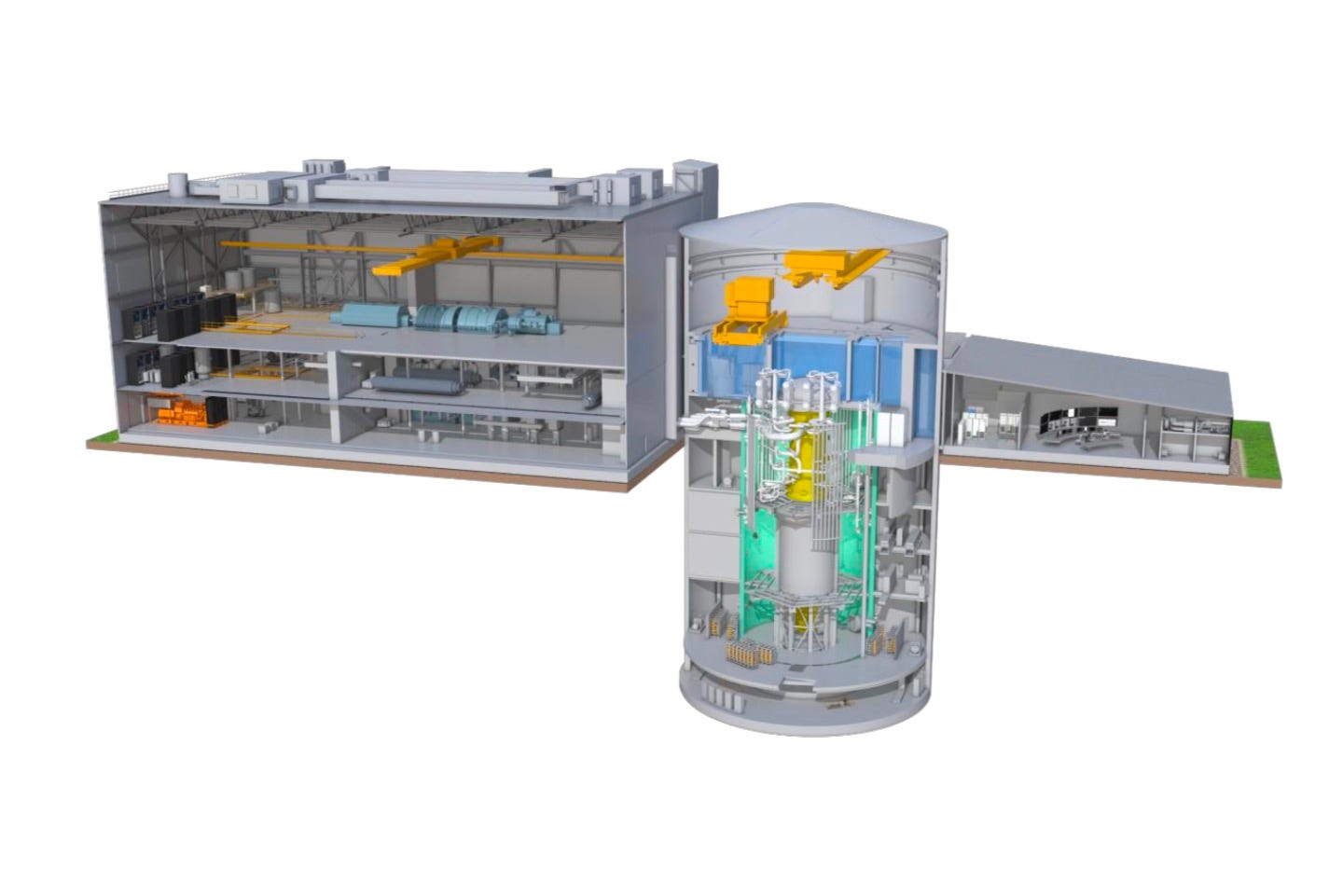

The result is a Reactor Pressure Vessel (RPV) that is extraordinarily tall — 26 meter for the BWRX-300. Compare with the Advanced Boiling Water Reactor (ABWR), which produces more than four times the electrical output but still has a shorter RPV at 21 meter.

“The civil works become large. The equipment becomes large. So cost will go up.”

How the BWRX-300 became obese

To accommodate the height of the RPV, it’s necessary for most of the BWRX-300 to be buried underground. The reason you can’t just put it in a tall building is because the spent fuel pool needs to be in line with the water level and you can’t have that just hanging out in the sky. And besides, the US Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC) takes aircraft impact risks seriously.

Here you have another problem: when you are digging down at some point you will hit bedrock. The problem is going to be different from site-to-site. This is going to add another layer of challenge to the goal of standardizing builds and reach the goal of costing down nth of a kind builds.

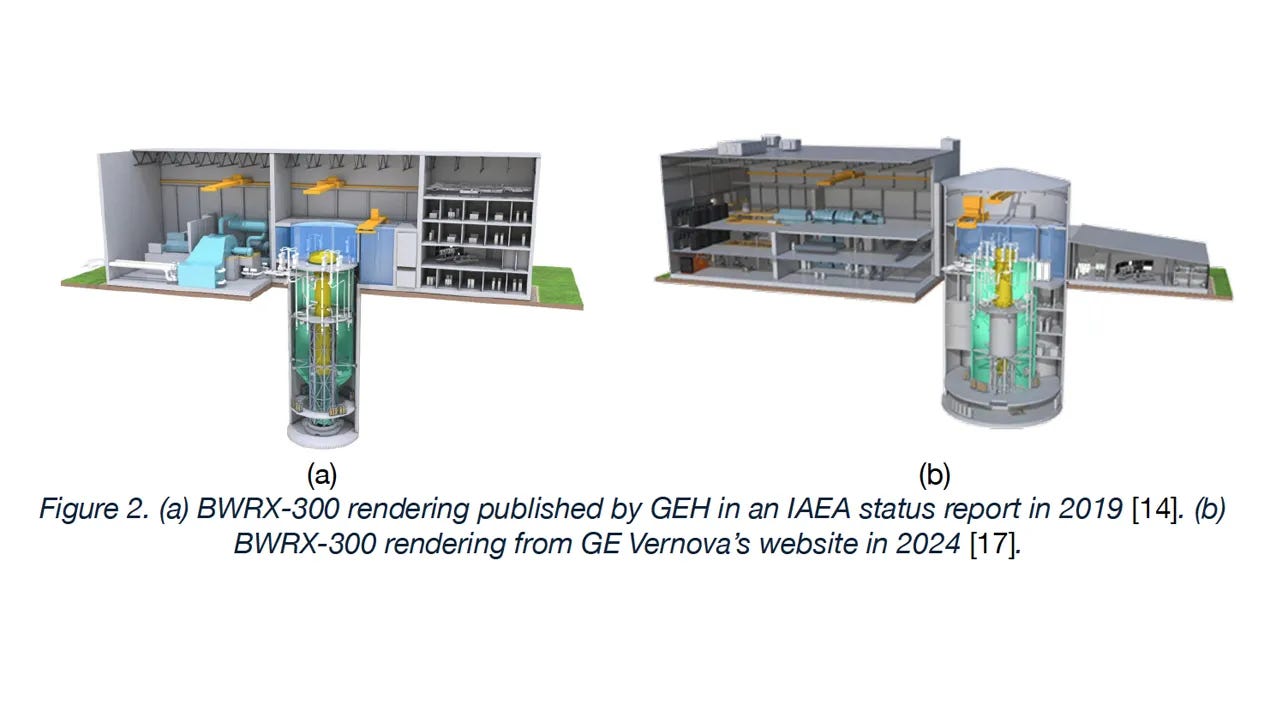

Initially when the BWRX-300 was derived from the much larger ESBWR, a lot of safety systems were removed to combat the diseconomy of scale and make the building structure around the reactor compact. Alas, this compact concept did not survive the regulatory process. As can be seen in the rendering above, the “well” holding the RPV became positively obese: 36 meters in diameter, too wide for the biggest boring machines, “wide enough to the exact same size as an ABWR reactor,” according to Shirvan.

The Elemental Take

I still believe that the BWRX-300 is the “closest thing to a sure thing” when it comes to being the first SMR to be completed. The Darlington project is moving, and given the strength of the team involved the late 2028 timeline is still looking good.

The consortium of companies taking part in the development of the BWRX-300 have done a lot right, especially in splitting the development costs so that no company ends up taking “the tip of the spear” for the first-of-a-kind. And indeed the reactor looks to have a future for those situations when 300MW is really going to be all you need.

Having said all that.

It’s becoming increasingly clear to me that when compared to the tried-and-tested ABWR, the BWRX-300 is quite a lot of squeeze for only a quarter of the juice. The civil work is considerably complex, will be hard to standardize from site to site, and at the end of the day will still be large.

It might be an idea to revive the ABWR, certainly for the places where we have demand for the load. As for locations where you don’t need 1,350MW, maybe it’s an idea to explore building data centers or hydrogen electrolyzers next door to use up the extra.

Is there information on why precisely the BWRX-300 reactor shaft grew so immensely?

Small reactor economics are especially sensitive to safety requirements. The best chance for small containment sizes to fully use the modular and small (!) idea without regulatory easing will be atmospheric pressure reactors: Liquid metal (especially lead) and molten salt reactors. Gas cooled graphite moderated reactors probably not so much. From what we have seen from LWR SMRs so far (AP300, BWRX-300, Nuscale), the containment building effort is just too big.

In my humble opinion, Nuscale is dead except for subsidized export projects. Best case, they can reuse the integrated power module with a different building/containment design and relaxed regulation in the future.

The FAA has different safety standards depending on the aircraft size and purpose. A good example for the NRC.

Have a look at this:

https://www.elidourado.com/p/personal-aviation

I recently read (I think it was from the IAEA) that there are about 70 SMR designs competing globally, but that there is movement seeking standardization. Amazon has made a big commitment to x-Energy's advanced SMR which uses TRISO-x fuel. Do you think they've made a wise choice? Or would you have chosen another type SMR design?