Japan’s atomic comeback?

Once the most efficient builder of nuclear in the world, can Japan’s nuclear industry ever return to its previous glory?

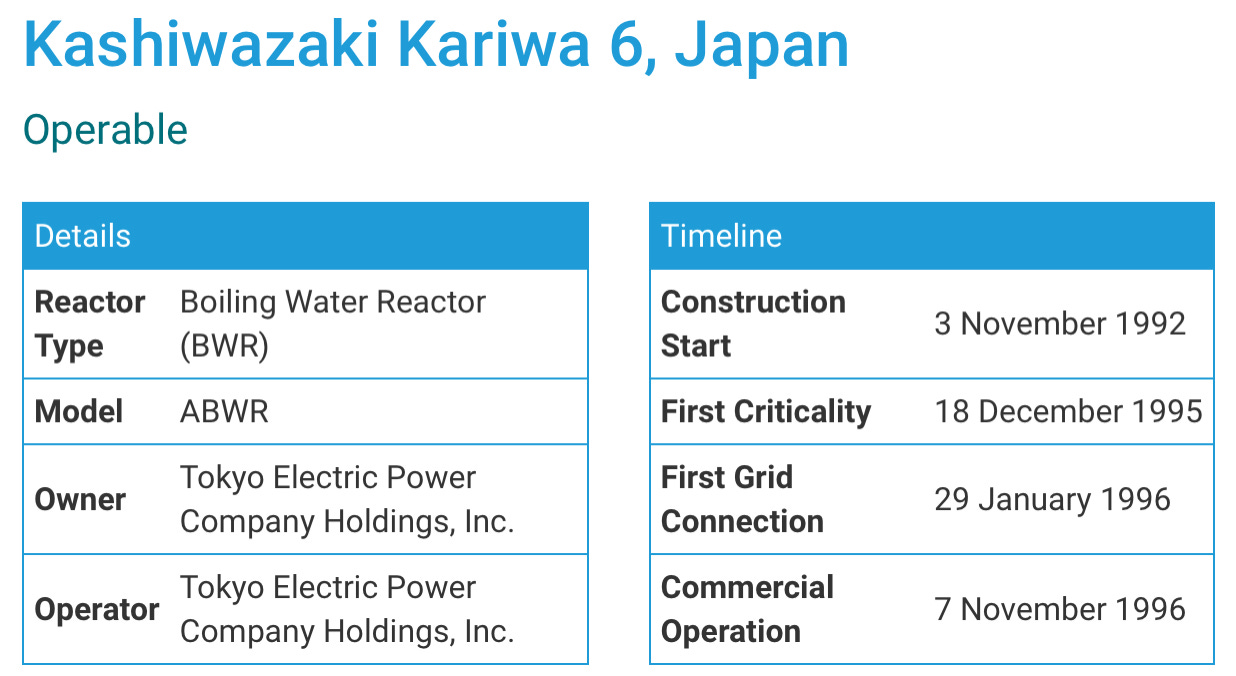

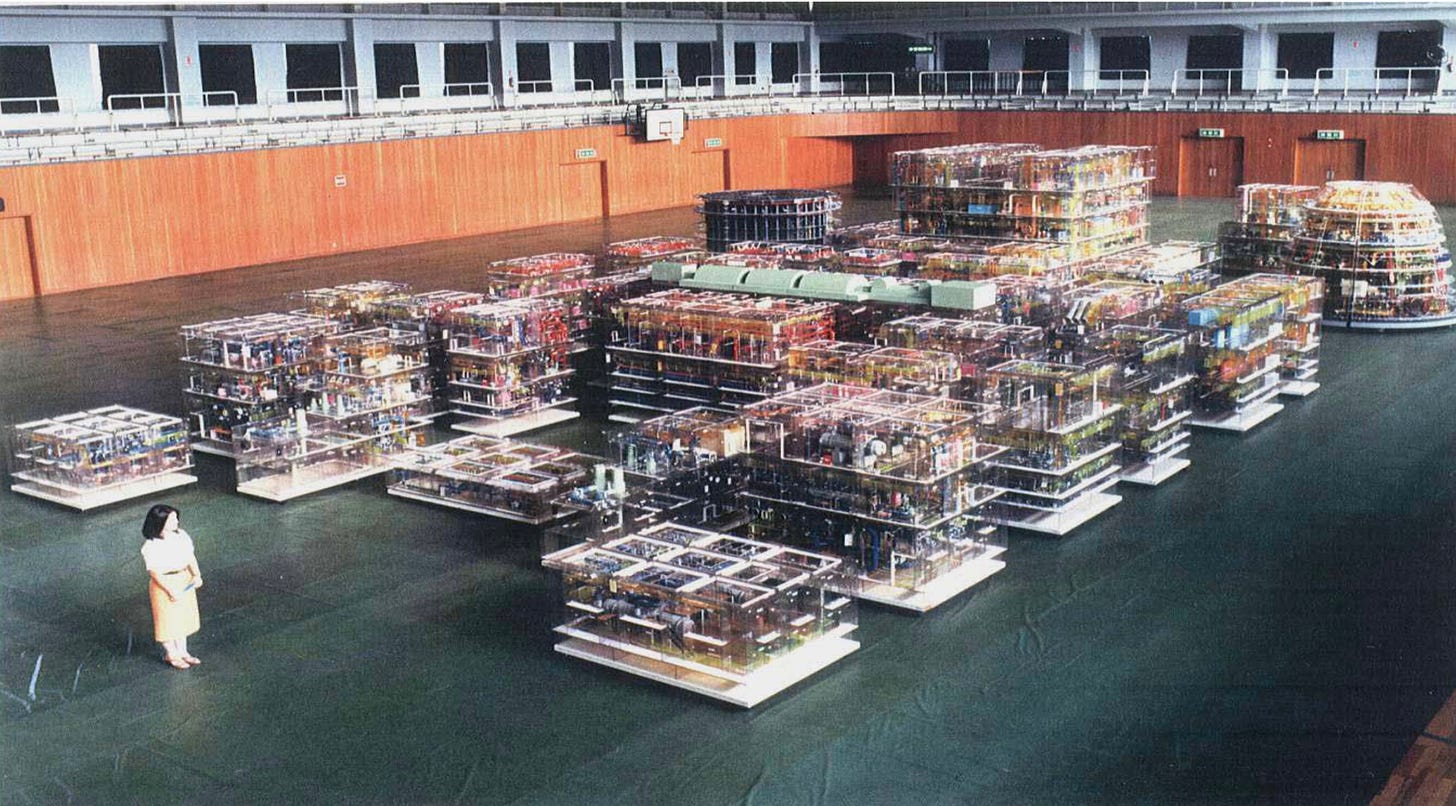

Japan used to be one of the most prolific and efficient builders of nuclear power plants in the world. Being energy resources poor but industrially ambitious, it was early to introduce American nuclear technology and indigenized the industry aggressively. In 1975, the Light Water Reactor Improvement and Standardization Program was launched to modify existing Boiling Water Reactor (BWR) and Pressurized Water Reactor (PWR) designs to make them bigger, better and safer. The effort bore fruit. Japan started knocking out high-powered, advanced nuclear power reactors with build times of around five years. The 1,315MW Kashiwazaki Kariwa Unit 6, an ultramodern ABWR (Advanced Boiling Water Reactor), was built in just three years, achieving commercial operation a year later.

By 2009, nuclear energy accounted for 29% of Japan’s electricity production. That number was set to increase to 41% by 2030 and 50% by 2050. Alas it was not to be. Everything came to a halt in the wake of 2011’s Fukushima Daiichi disaster. Japan’s entire nuclear fleet of 54 operable reactors were shut down.

The long road back

Despite the stated effort in 2014 to bring nuclear generation back to 20-22% of Japanese electricity generation by 2030, it’s been a long and arduous journey to turn plants back on again. Ten nuclear reactors are currently in operation in Japan, accounting for approximately 6 percent of the energy mix only.

To replace the missing nuclear, Japan pivoted hard to LNG and ramped up renewables, both of which comes with complications. Japan has joined western countries in sanctioning Russia, meaning it needs to find a way to get off cheap Russian gas while LNG prices are through the roof on European demand. (And let’s not forget, as many do, that natural gas is still a fossil fuel despite being less bad than coal.) Meanwhile, renewables remain expensive in Japan and there’s a question mark over how much more of it the grid can digest.

A stark reminder of how untenably tight the power supply has become came on a cold day in March this year when Japanese authorities had to issue its first power shortage alert. Tokyo came within a hair’s breath of blackouts, and was only saved thanks to extraordinary measures to conserve power that included newscasters presenting their stories under dimmed lights.

No wonder Japan’s Prime Minister, Fumio Kishida pledged to turn the country’s idled plants back on as quickly as safely possible. But Japan is still saying ‘no’ to nuclear new builds. “We will make the most of what we have,” said Economic, Trade and Industry Minister Koichi Hagiuda.

If everything goes as the Japanese government wishes, the country’s energy mix in 2030 might look a little bit something like this:

Thwarted export ambitions

Even after the Fukushima Daiichi disaster, Japan continued to try and push through nuclear exports, but one after another, projects in various stages of maturity in the Vietnam, UK and Turkey were cancelled. Perhaps it’s not a surprise that other countries would question Japan’s technology given that they’ve given up on building more plants at home. It’s too bad. Given how ABWRs like Kashiwazaki Kariwa #6 were coming in on-time and under-budget, one can easily imagine an alternative future where Japan became a nuclear export powerhouse. Before Fukushima, Hitachi alone had plans to construct 38 overseas plants by 2030. The market came to prefer PWR technology, further putting Japan’s offering of ABWRs at a disadvantage. The last ABWR to come online, Shika 2, did so in 2006. With no new projects either domestic or overseas in the pipeline, the once-promising design seem destined to fade from view.

I asked Professor Yeh Tsung-kuang of Taiwan’s National Tsing Hua University whether there is a possible way back for Japan’s nuclear export industry.

“Unlike Korea where the leadership is backing the nuclear industry to the hilt, including restarting exports, I think Japan is more concerned with making sure there is enough power to supply their domestic needs,” said Professor Yeh, “I don’t think there is the political support or the commercial appetite for whole-plant exports. However, Japan’s nuclear industry will continue to play an important role world-wide through their US-collaborations.” Hitachi is in alliance with General Electric while Mitsubishi Heavy Industries has long-standing technical partnerships with Westinghouse.

Compared to the US, which suffered from a 4-decade drought in construction starts, Japan’s supply chains for parts such as reactor vessels, fuel rods and cooling pumps are not so atrophied. This means while Japan no longer have the ambition to export whole nuclear power plants at the moment, it’s still a formidable maker of components. With the world turning away from Russian and Chinese supply chains, Japanese components makers will likely find a rich market supplying both parts for new builds and in parts replacement and maintenance.

Research and Development for a new future

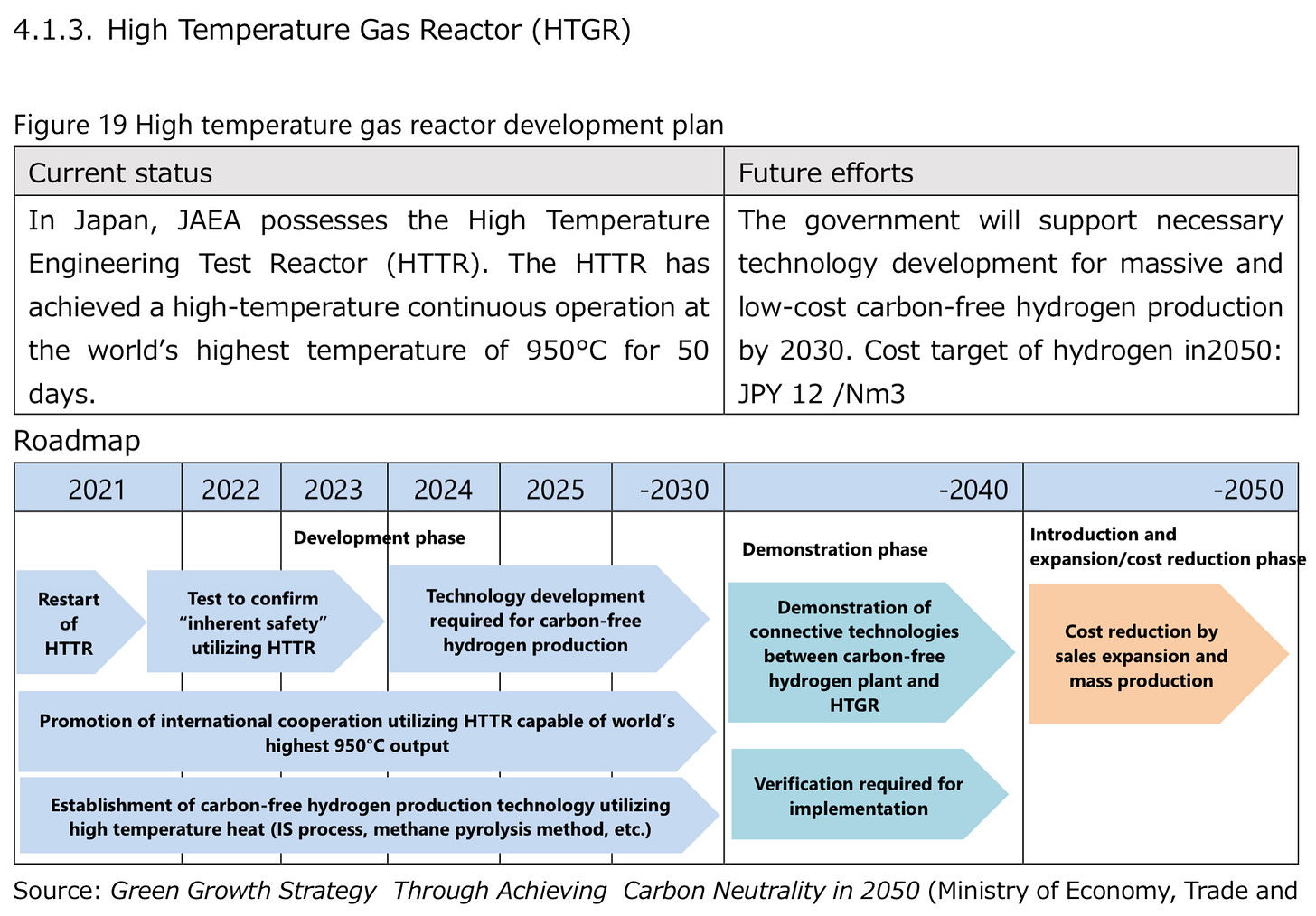

According to the Japanese Ministry of the Economy’s “Green Growth Strategy” document, released 2021, Japan has not completely abandoned R&D in nuclear energy. Small Modular Reactors, Fast Reactors and fusion all gets some love and and a roadmap that goes to 2050. However, the most exciting area in R&D appears to be for High Temperature Gas Reactors (HTGR):

Out of all four roadmaps, the next-steps for the HTGR appears to be the most concrete. The 30MW experimental High Temperature Engineering Test Reactor (HTTR) has been successfully restarted. The next step, after testing to confirm the “inherent safety” of the technology, would be developing the technology required to tap HTGRs for hydrogen production. This dovetails closely with Japan’s stated ambitions to go big on hydrogen.

THE ELEMENTAL TAKE

The Japanese atom, more than that of any other nuclear industry in the world, demonstrated how it is possible to build nuclear plants fast and on budget through relentless standardization. It was able to do so well into the 2000s. The next time it’s argued that nuclear is too slow, never on budget, can’t be done in a modern democratic country efficiently etc etc, remember it WAS done…less than two decades ago.

Support for nuclear energy is rising. In March, for the first time since Fukushima, the majority of Japanese again supported nuclear power. We can expect more legacy plants to re-open. Japan’s role as a supply-chain player supplying critical parts to the nuclear industries of the world also seem secure. As an example: only four countries currently have the heavy forging necessary to make large reactor vessels: Japan, China, France and Russia.

It’s a shame that the industry’s efforts to keep the ABWR lineage alive through exports after the trauma of Fukushima have failed. The Japanese government appears to have no desire to revive it. Instead, we have rather preliminary research and development going in several different directions.

While I wish all of those efforts well, the straightest path to energy security and a decarbonized future for Japan surely would have been a straight-forward resuscitation of ABWR (and APWR) development. Their size and speed of deployment will not be matched for quite a while.